Pasture Champions: Bill and Cath Grayson from MBCGC 3/5

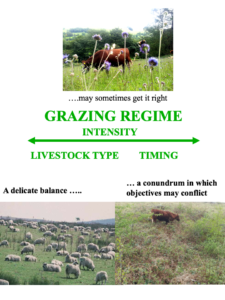

Grazing regime

Grazing regime

How it is connected across the farm and beyond?

Because we don’t farm a single enclosed holding, establishing direct connectivity between the different habitats that we manage is much harder to achieve than it would be if all these sites were closer together. Connections linking them do exist however, but these are more conceptual than actual and emerge from having to integrate the different grazing needs of the various sites into one coherent grazing plan that ensures enough suitable animals will be available each year to deliver the grazing for each individual site at the prescribed time.

Each site may contain a range of different habitats which the livestock will be able to move through as they seek out the best areas to obtain feed, shelter and rest. Seeds can easily get moved between these different areas, carried on the feet or in the coats of the grazing animals. Such freedom of movement can obviously make it easier for plants to colonize new areas, wherever there are suitable conditions for their establishment. This provides a convenient and cheap means of enhancing the species richness or vegetation structure of the different habitats.

We regularly see sapling trees and shrubs germinating in the pastures we graze, some of which will eventually go on to establish a new generation of young trees and shrubs, The seed from nearby patches of woodland or scrub is able to germinate in the hoof marks left by the cattle as they move amongst these different habitats, alternatively grazing and browsing. Such natural processes seem likely to have important benefits in promoting expansion of tree cover by natural regeneration, something that is of particular relevance to many of our upland landscapes and which is described in more detail below.

It has already been explained how we are making more deliberate connections between different sites as specific pre-planned measures for restoring species-rich hay meadows. So it is encouraging to see similar tactics being adopted by other local stakeholders, wanting to expand the benefits of species-rich grasslands into the wider landscape of the Arnside and Silverdale AONB. We are helping staff from the AONB who, having secured funding from Plantlife as part of their Meadow Makers scheme are using one of our restored meadows as a donor site from which to harvest a suitable seed mix for restoring flower-rich hay meadows on neighbouring holdings. This donor meadow of ours had itself received the same restoration treatment described previously. The fact that it is now, just ten years later, considered a good site from which to harvest a suitably representative seed mix for the area shows how well it has worked, having initially consisted of a rather species-poor sward, dominated mainly by grasses and containing few flowers or herbs

What are the benefits to the farm?

It’s fairly obvious that our ‘farm’ operates in quite a different way to most other agricultural holdings, but the fact that it has survived for nearly thirty years seems to indicate that our business model is a viable one. It pre-dates the introduction of Single Farm Payment, but coincided with the launch of the first Countryside Stewardship Scheme back in 1992. This was when farmers were first able to be paid to manage land in ways that benefited wildlife and landscapes, a step that paved the way for conservation graziers to be rewarded for using their animals to deliver the management objectives set out in these kind of agreements.

We have been able to benefit both directly and indirectly from these schemes. The direct benefits come from being able to enter some of the land we rent into a stewardship agreement in our own name so that the annual payments are made straight to us. However, the larger part of the system is let to us on terms that prevent us applying for Stewardship directly. In such cases, it is the landlord, usually one of the local conservation organisations like the RSPB, Wildlife Trust, Woodland Trust or Butterfly Conservation, who will enter the scheme and receive the payments in their own name. However we are still able to benefit from such arrangements because fulfilling the terms of these agreements inevitably requires that the site be grazed, and in a particular way that is expected to deliver the scheme’s environmental objectives. This however, is something that these organisations, without their own livestock, are unable to do - which is why they depend on the services of a conservation grazier like us.

Managing habitat for butterflies

Managing habitat for butterflies

In return for explicitly committing to graze the livestock in accordance with whatever grazing regime is required under the terms of the Stewardship agreement, we are only expected to pay a nominal rent for the use of the land. This is because the poorer forage quality, the additional physical challenges posed by the rougher terrain and the sometimes inconvenient conservation-led clauses associated with these situations make them less viable in commercial farming terms. But at the same time we are allowed to claim the Basic Payment for the site, an arrangement that makes for an equitable arrangement, based on dividing up the various area payments between ourselves claiming payment for the farming element and the site managers getting the conservation payments. This creates a stable relationship in which each party depends on the other one sticking to their side of the agreement so that both are eligible to receive their respective payments each year.

Of course, we are only too aware that this convenient dovetailing of the current area-based payments is about to be phased out, and much is still not known about how the new Environmental Land Management schemes will restructure the different layers of support available to farmers and land owners. However we are quietly confident that the level of trust and mutual interdependence that has been fostered under the current arrangements will ensure that our conservation grazing activities will continue to be properly rewarded.

Although this specific remit to deliver biodiversity benefits has helped to secure the viability of our particular business, conservation grazing may not suit everyone.

Many farmers’economic fortunes depend mainly on market forces , a focus that forces them to prioritize improving yield and efficiency of production.

Such farmers would probably find it harder to justify taking on these ‘unimproved’ pastures, full of wild plants of unknown feed value and safety. They may be concerned about reductions to yield, slower livestock growth rates which could run the risk of missing financial targets critical to their business.

However we firmly believe that what these wild herbs may lack in terms of quantity of yield is more than compensated for in terms of their better nutritional quality.

This is since we became aware of how much our cattle prefer hay that is rich in herbs and wild flowers. We noted their eagerness to get the darker colour material that indicates that haylage contains a lot of herb. Many herbs take on a dark colour, almost black, when cured for haylage – a change that the cows appear to have noted too.

Besides being more palatable, we have found wild herbs to be more nutritious. Separate samples of herb and grass sorted from within the same bale and sent for testing in the lab have shown that the herb component is higher in protein, energy, minerals and trace elements than the grasses accompanying them. This is likely to be particularly important for farmers like us, who because of agri-environment prescriptions cannot cut their meadows for hay until later in the season, by which time feed value of the grasses is in steep decline. Having a higher herb content ensures that even hay made late in the season can still provide a good source of nutrition on which to rear young stock through the winter.

CONTINUE...