Pasture Champions: Bill and Cath Grayson MBCGC 2/5

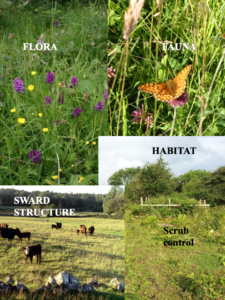

Flora, fauna, sward structure and habitat

Flora, fauna, sward structure and habitat

What do you do to encourage this biodiversity and what are the lessons you've learned and would like to share?

Back in the early 1990s when we started out, many of the reserves that our cattle now graze had long been abandoned by farmers because they could not sustain sufficient levels of production demanded by an efficient farm business.

Despite the best efforts of the conservation bodies that by now were managing them as nature reserves, they were gradually losing much of their original diversity as the grasslands became increasingly dominated by just a few of the coarser grass species, the rank growth of which smothered the more delicate limestone flowers and herbs.

These are the same flowers that give limestone grassland its unique ecological value, providing important food sources for a wide range of insects whilst creating a fantastic display of beautiful colours and textures – something that the poet John Clare referred to as his ‘midsummer cushion’.

Amongst the attractive limestone flowers that suffered this decline were species like dog violet, cowslip and rock rose, all of which provide an essential food supply for certain butterflies like the high brown and pearl bordered fritillaries, the duke of burgandy and the northern brown argus, respectively. All of these butterflies have become rare throughout the UK over recent decades, due to loss of habitat, usually driven by changes in farming systems.

By the time we had begun to reintroduce livestock grazing to these habitats, many of them were already experiencing a rapid expansion of woodland and scrub.

This was due to natural succession, the process by which these woody species are able to colonize open ground by dispersal of seeds and spread of root-suckers, once they had been released from the constraining impact of browsing animals.

All these trees and shrubs are native species and most of them are very important ecologically, supporting their own assemblages of smaller plants and animals. Some, like the juniper, are important species, requiring conservation in their own right whilst others like oak, buckthorn and blackthorn are important food sources for particular butterflies like the purple hairstreak, brimstone and brown hairstreak respectively, all species that are regularly recorded on sites that our cattle graze.

The loss of open habitat appears now to have been halted since the grazing has been restored, suggesting that the browsing impact of the livestock has helped to establish a new and more stable dynamic between the competing processes.

Cattle are especially important in this respect, having the physical strength and bulk to break up denser areas of scrub to create the smaller gaps and glades that many of these shelter-loving butterflies need in order to thrive.

The complex mixture of shaded and open habitats that develops under this form of grazing is usually termed by ecologists as ‘wood pasture’.

These days, wood pasture is generally regarded as the most likely type of landscape to have predominated in Britain before farming got underway. And because its mosaic nature provides an abundance of ‘edge habitat’ upon which many of our most specialized and sensitive native species depend, it is usually highly valued by conservationists.

How does it work?

How does it work?

This ability of native trees and shrubs to naturally regenerate and spread to new areas is an important consideration because of the world’s urgent need to mitigate climate change by capturing and storing excess atmospheric carbon.

Trees and other types of vegetation are still our best hope for achieving this – and what’s more they do it for free.

So it is interesting to note that although we started our conservation grazing operation by using cattle to check the unwanted spread of woody plants on sites where succession was a problem, it evolved to one that could also facilitate their expansion by natural regeneration in situations where this is appropriate. Such circumstances occur on the Ingleborough National Nature Reserve (NNR), in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales, where decades of continual sheep grazing had eliminated much of the tree and shrub cover.

In 2003, English Nature (now Natural England) who manage most of England’s NNRs had decided that the site’s conservation value could be enhanced if the landscape were to begin acquiring more trees and shrubs. They realised that for this to happen, cattle would have to be brought in to replace the sheep. Which is where we first became involved with the site, taking on this new challenge when none of the local farmers could be persuaded to take it up.

And for us it was a genuine challenge as in many ways the situation was the direct opposite of what we had been dealing with prior to that down on the fringes of Morecambe Bay.

So it was really exciting to see within the first year or two of the cattle taking over the land beginning to respond to the new grazing regime, with flushes of the pale pink birdseye primrose and bursts of bright yellow rock rose appearing across large swathes of the open expanses of this upland rough pasture.

Managed trampling at work

Managed trampling at work

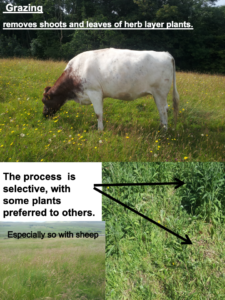

But as well as this impressive display of flowers in full bloom , we soon noted how, wherever mature trees and shrubs were still present, we began seeing young saplings of hazel, hawthorn and ash emerging from the sward. These were obviously the progeny of the nearby trees, having germinated in gaps created in the sward by the cattle’s hoofprints. And whilst many of these new recruits do appear to get browsed off by the cattle, a proportion are managing to escape this fate long enough to establish themselves as permanent constituents of the community. Hopefully, this will ensure a new and more widespread generation of trees will be ready to take over from their parents as the latter begin to die off.

The cattle grazing on Ingleborough has worked so well over the last 18 years that Natural England have just bought a large area of new land adjoining the reserve with the intention of expanding this form of management. Their aim is to expand the cattle herd, plant clumps of trees to provide a suitable seed-source, and then wait for Nature to deliver her own version of upland wood pasture. Perhaps, given time, this might come to resemble the kind of landscape that would have existed here before the first farmers arrived and began clearing it of trees.

Our efforts to restore biodiversity are not just confined to grazing of pastures; we also manage a suite of hay meadows, all of which have been or are being restored to a much more species-rich state than when we took them on. In all, there are about 20 ha of what had been either improved or semi-improved grassland back in the 1980s, some of it having been ploughed and re-seeded with a commercial ryegrass-based mix. One had even been a market garden for many years, receiving such high levels of inputs, that even today it still has the astonishingly high phosphate index of 5. Even more amazing then that this field is now our most stunning example of a wild flower meadow, with wall-to wall orchids and a host of the other colourful species that are typical of long-established hay meadows. The dozen or so meadows that we manage are scattered across the Arnside and Silverdale AONB, an area that despite its plethora of limestone grasslands had virtually no examples of species-rich hay meadow when we started farming here. It therefore came as no surprise to us to learn that 95% of Britain’s traditional flower-rich meadows have been lost since the 1950s.

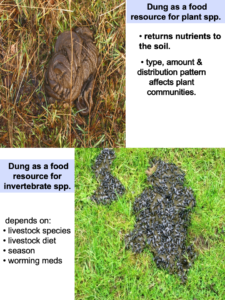

Benefits of dung

Benefits of dung

A conservation grazing system, like ours might not be expected to have much need of meadows or for the hay crop that they produce, since most of the animals are outside grazing these different habitats throughout the whole of the year. However there are times every winter when we need to provide additional feed some of the animals, either because the quantity or quality of the grazing has declined to a point that threatens to compromise their welfare or because prolonged periods of snow or flooding have made the grazing inaccessible. Our ongoing need for winter fodder is best met by making it ourselves, so that we have more control of its quality and provenance. We especially value fodder with a high content of herbs, because it appears to be what the animals themselves prefer and to perform best on. All of which emphasises the splendid synergy that exists between the needs of the livestock and the benefits for nature conservation.

The method we have evolved for restoring plant diversity is straightforward, low-tech and cheap. It involves keeping a small group of cattle on the target meadow and feeding them with hay taken from another more species-rich donor meadow. Seeds of the required-mix of plant species are brought in in the hay bales which are scattered loose on different sections of the field each day. Most of the seeds fall out when the cattle are eating the hay and are trodden into the soil surface where some will germinate the following spring.

Hay rattle, is a keystone species in this restoration process, because once established it parasitizes and weakens the more dominant grass species, a result that many would think fundamentally contradicts the basic farming ethic. Why would any self-respecting farmer choose to undermine their own productivity like this? And certainly we do expect to see the number of bales decline quite significantly in the first two to three years following establishment of the hay rattle. Soon, however, other herb species, freed from the smothering effects of the coarse grasses, thanks to the arrival of the hay rattle, are able to establish and spread. And usually, one of the first herbs to take advantage of the new dynamic is red clover, a legume that, by fixing nitrogen from the air is able to boost plant growth, rebalancing productivity of the sward by compensating for the weakening effect of the hay rattle.

A new equilibrium is soon established in which these opposing effects of the clover and the rattle usually reach a balance at something aapproaching 80% of the original yield. And whilst the loss of a fifth of the hay crop is not insignificant we still regard the change as a positive one overall because the feed-quality of the herb-rich material is superior. Laboratory analyses have confirmed that the herb component of a sample of hay is more nutritious in terms of its energy and protein supply, and its mineral and trace element content compared with the grass portion. We believe that the high proportion and diversity of herbs in their diet explains why our cattle are able to thrive as well as they do on what most farmers would consider to be a less than adequate diet.

But, although, we have to accept that not everyone will be convinced about all this ‘biodiversification’ in terms of its benefits for animal husbandry, the advantages for nature conservation are unquestionable.

Once the hay rattle and red clover are well established we are able to leave Nature herself to work out how the rest of the restoration process proceeds, allowing new species to arrive and take hold as they ‘want’ to, rather than best guessing her choices by introducing species that we think ‘ought’ to be there. This necessarily means that things can take longer than they would if we just planted a ready-made herb-rich seed mix, but we feel that the end result of letting Nature take her own course feels more valid and is more likely to be sustainable.

We began this process back in 1993 with a half dozen ‘improved’ meadows that, having received regular dressings of NPK fertilizer in the past, by then contained few flower species. apart from a single field that held a small clump of hay rattle tucked away in one of its corners. From this not-very-promising start we have managed to restore a rich mix of herbs and flowers to more than twenty meadows using a method of our own devising but which is similar to what is now might be termed ‘bale-grazing’; somehow, it seems our home-made, rather ad-hoc system developed into a recognized technique for increasing plant diversity in grass swards.

After a few years, even the untrained eye can see that these meadows of ours, with their colourful mix of wild flowers, which might include species such as knapweed, ox-eye daisy, meadow vetchling, betony or tufted vetch look utterly different to the uniformly green silage fields that are typical of the more intensive livestock farms that these days occupy most of the more productive land surrounding Morecambe Bay.

Grazing at work

Grazing at work

A few of our meadows have even been colonized by orchids, a particularly significant group of indicator plants denoting high-nature value sites, since they require the presence of specific types of symbiotic mychorrizal fungi in order to colonise a site. These mycorrhizae quickly disappear when modern agro-chemicals begin to be used, making such situations untenable for orchids.

So our excitement might be imagined when, in 2011, one of our most long-standing ‘restoration’ meadows produced a single spike of northern marsh orchid and how that excitement has increased throughout the ensuing ten years as we watched the population of orchids increase.

It now numbers more than two hundred plants that have spread their deep pink spikes of flowers throughout the whole two acre field, making a glorious sight when they bloom in June each year, a sight that seems to become increasingly splendid with each passing year.