Pasture Champions: Bill and Cath Grayson from MBCGC 5/5

Meadow ants and grazing livestock

Meadow ants and grazing livestock

What lessons have you learnt and would like to share with others?

When we first began our conservation grazing journey, we were motivated mainly by a desire to enhance wildlife and natural habitats, an aspiration that we have been extremely fortunate to pursue for the last 30-plus years.

However, as time has passed we have come to realise that Nature will never be able to truly flourish if it is restricted to the narrow confines of designated areas and reserves, whilst continuing to be undermined throughout the remainder of the countryside.

The startling fact that the drastic declines in insect abundance, that have since been referred to as ‘insectageddon’, were first recorded on nature reserves, clearly emphasises the starkness of this reality; these are the very places where biodiversity ought to still be able to thrive.

This should serve as a wake up call for conservationists; instead of focussing all our hopes and efforts for nature recovery on protecting the few special high nature-value areas and habitats that are left, we should be extending the area of concern more widely.

And the best place to start building a stronger conservation ethic would be within the food and farming system, itself; our very own life-support system and the one that is most reliant on Nature playing her full part.

This, we feel, is the most reliable basis for delivering the ‘One health’ agenda: healthy soil, healthy food, healthy people, healthy planet.

Restoring nature-friendly approaches within the wider farming landscape is important for conserving those specialist plants and animals that have lost out as traditional farming methods have been replaced by modern intensive systems.

But moving towards a larger-scale adoption of agroecological methods is needed to halt the decline of all forms of wildlife low-input extensive species and habitats that have adapted to thrive in such a setting but also for providing the world’s people with the healthiest supply of food, free of chemical residues and without compromising future generations.

Top-down approach

Top-down approach

The loss of insects from the very areas that are being specifically managed to conserve wildlife shows that a land ‘sparing’ approach is unlikely to fully protect Nature; intensive chemical-based farming within the surrounding landscapes has adverse impacts within such reserves.

So whilst we have always avoided all forms of chemical inputs when managing these high-nature value sites, we didn’t realise at the outset the essential importance of wholesale agro-ecological transformation for our wildlife to be able to survive. We now see that the need for such a change has become increasingly urgent as the world begins to confront the co-emergencies of climate change and ecological collapse.

Although we have been farming organically for 30 years, it is only within the last ten that we have come to realise the contradictions inherent in feeding grains to ruminants.

Whilst this obviously clashes with the basic agroecological principle that grazing livestock should be fed their natural herbage diet, it also represents an enormous waste of resources, when up to a third of all the world’s cereal crops are fed to animals rather than supplying human food needs directly.

Realising this simple fact is what drove us to become Pasture for Life-certified, a commitment to using only pasture or pasture-based forage to feed our cattle and sheep.

Extra certification of course represents an additional cost but one that we feel is justified given how well Pasture for Life accreditation dovetails with our existing organic status.

Having started this journey investing all our efforts and focus in management of specific nature conservation sites, we have come to realise the crucial need for a wider promotion of a more holistic systems-based agroecological approach that would be better able to conserve biodiversity across the whole farmed landscape.

And whilst we feel that it is important that farmers everywhere should respond to this call, we understand only too well from direct experience why current economic and political pressures are making this difficult.

So perhaps the best advice we could offer to other farmers would be to urge them to make time to carefully consider how they might adapt their business ethos and farming practices to take full advantage of the new ‘public money for public goods’ system of farm support.

It is absolutely clear that the majority of small and medium sized farms will struggle to remain viable once the current Basic Payment has been removed.

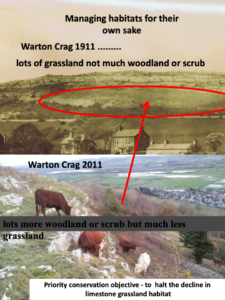

Managing habitats for their own sake

Managing habitats for their own sake

Many such businesses will face a stark choice of whether to adapt their farming methods to benefit from the new environmentally-friendly support system or go all-out for maximum production. There will be no shortage of voices from a range of vested interests within the UK’s food system stakeholders urging them to boost productivity by increasing their use of purchased inputs.

However, such a strategy, is unlikely to succeed because the prices for most types of farm produce have declined in real terms, relative to the cost of the fertilizers, seeds, chemicals and feed that provide the means for cranking up output.

This means that a farm’s overall profitability begins to decline as purchases of these externally sourced inputs increase, a situation that is described and explained in a report, appropriately entitled ‘Less is More’.

Faced with the difficult choice about whether to opt for a productionist or an environmental agenda, our hope would be that before deciding which way to go, farmers will be able to invest enough time to assess their business prospects in a similarly critical way.

Hopefully they might then realise that their farming profitability will, in fact, best be served by reducing inputs to levels that are commensurate with the carrying capacity of their land - or as it is termed in the report: Maximum Sustainable Output (MSO).

Adopting the ‘Less is More’ approach should also have the additional advantage of boosting each farm’s prospects for securing the best level of support from the new post-BREXIT farm payment schemes, which in all four of the home nations, seem to be broadly aligning themselves with public goods delivery.

This should provide a powerful win:win message to help motivate both farmers and conservationists, to collaborate in paving the way for an exciting transformation of the UK’s food and farming system.

If sufficient numbers of farmers were to adopt these principles we could begin the move towards a ‘One Health’ food system consisting of healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals and healthy people, one that was underpinned by natural processes rather than being undermined by man-made chemical intervention.

A food system model recently devised by IDDRI on behalf of the FFCC has already demonstrated how such a nature-based approach could become a reality.

It shows how applying tried and tested agroecological principles to current farming practice, combined with a more strategic approach to land use and a switch to healthier diets for people could restore nature, cut greenhouse gas emissions, cease pollution and produce healthier, better balanced supplies of indigenous food in quantities sufficient for our needs.

This model as well as providing a blue-print for transforming our own food system also serves as a call for action, not just for farmers but to the whole of society, a society that is having to confront the combined existential threats of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Let’s wish ourselves good luck.